Do you have pain while you run?

For some of us, running is a simple and enjoyable task that we love to do on a weekly basis. But for the rest of us, running is something we dread and at times brings about pain in our hips, knees, ankles, and feet. This is a problem, but if you’re reading this you’re in the right spot because if you have pain while you jog, run, or sprint the fix might be easier than you think. Why do I have pain? Let’s first try to simplify why we might be having pain. When we go from walking to running, one of the biggest changes that occurs is that we literally leave the ground and are in flight during a running stride. Since gravity exists, what goes up must come down, and the result is higher striking and landing forces during running than when we are walking.

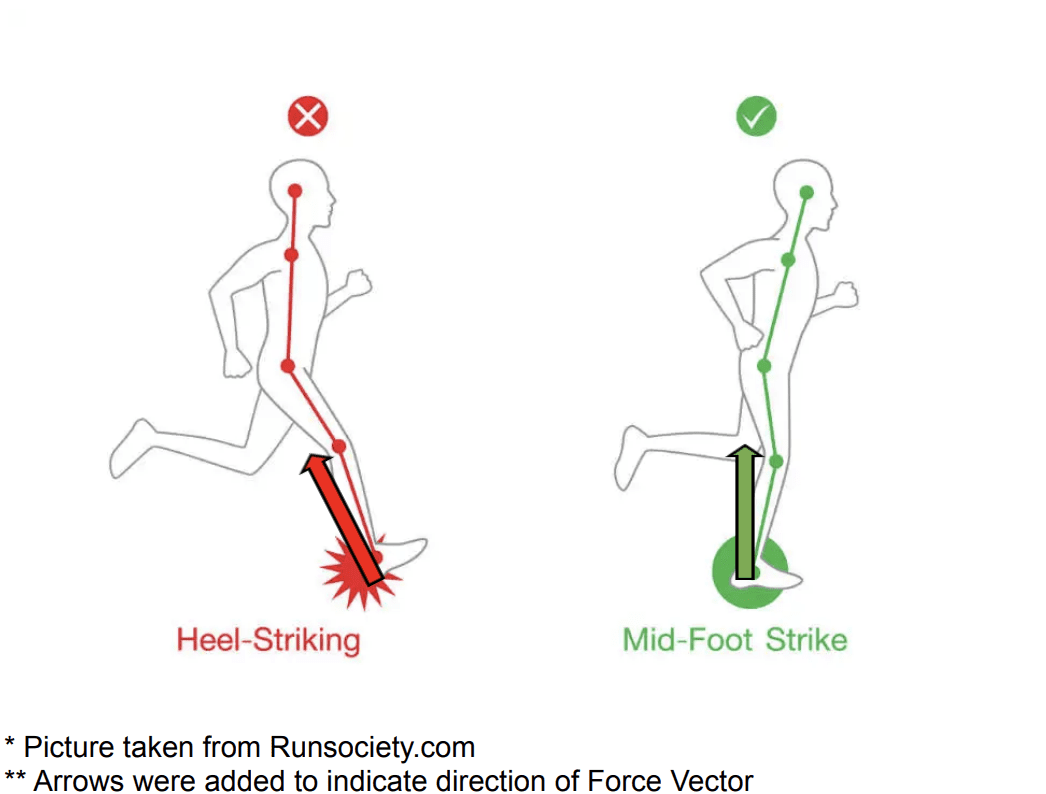

What I’ve seen most in the clinic is that a lot of runners who have pain when they run tend to be what are termed “Over-striders”. These types of runners tend to strike the ground with their lead foot landing in front of their body, making them strike the ground with their heel. Striking the ground with our heel in front of our body not only sends the force backwards into us and slows us down, but it limits the amount of support the gastrocnemius and soleus (your calf muscles) provide in absorbing the force. When the calf muscles aren’t absorbing those forces, there is a higher reliance on the knee and hip muscles to take over the job. If this continues, running efficiency breaks down and the forces then become too much for the muscles and joints to take on which in many cases can lead to pain, stress fractures, meniscus injuries in the knee, and labral injuries in the hip. So how do we reduce the amount of impact our legs take when we run?

How do I prevent pain and running-related injuries?

Luckily, there are a few ways to prevent pain and running-related injuries. The first way, and arguably most important, is to practice striking the ground underneath your body rather than out in front. Doing so helps to transfer the force up rather than before when the force was directed backwards, which now creates more of a propulsive force rather than a breaking force (see pictures below for a breakdown). Another reason why this is helpful is it then becomes easier to strike the ground with more of your midfoot vs your heel, allowing you to absorb the forces first by the calf muscles before distributing the forces to the knees and hips. The second way we can reduce the impact is by increasing your running cadence.

This is just a fancy way of saying “increasing the number of steps you take in a minute”. It sounds counterintuitive, but by speeding up your running cadence you help to decrease the contact time you make with the ground and increase the amount of shock absorption. Both are big time players in helping to reduce running-related injuries. The easiest way I’ve found to calculate my cadence is by counting how many times my right foot contacts the ground in 30 seconds and then multiplying that by 2 for how many left and right foot steps in 30 seconds and then multiplying that number by 2 to get how many steps in a minute. For example, if in 30 seconds I count 40 Right foot steps and times that by 2 I get 80 total steps in 30 seconds. Then I multiply that by 2 to get steps per minute and I’m left with 160 steps per minute. Most say that a cadence of 180 steps per minute is ideal, but try shooting for something around 160-180 steps per minute and work from there. Easiest way to practice this is to listen to fast-paced music or choose the 180 bpm playlist on your spotify or apple music account.

Lastly, monitoring the amount of running volume throughout the day/week is a major contributor for reducing and preventing pain while running. A good rule of thumb in progressing your weekly volume is to make <10% increases in your TOTAL weekly mileage. Therefore, if you ran 10 miles in a week, the most you should run for the following week is 11 miles (1 mile is 10% of 10, therefore giving you 11 miles). Another rule of thumb is to make sure your long runs are <30% of your total weekly volume. This means that if you’re going to run 10 miles for a given week, the longest run for that week should be no greater than 3 miles (3 is 30% of 10). On top of monitoring the mileage, it is equally as important to give yourself ample amounts of rest (at least 1 day a week). This can be a day of active recovery where you walk around your neighborhood and do some light stretching, or can be a full day of rest and relaxation to let your body reset. If you follow these 3 guidelines of striking underneath your body, increasing your cadence, and monitoring your weekly mileage you might notice some dramatic changes in your symptoms (in a good way). However, if you start to notice that even with these changes your pain does not get better or is gradually getting worse over time, you may want to consult your primary care physician or your physical therapist for further evaluation.