Baseball season is around the corner so we’re going to take a look at five ways that we can reduce your athlete’s risk of injury and set them up for optimal performance. This article will focus on pitchers that are still growing or are not yet skeletally mature (ages 11-21). Injuries like avulsions and apophysitis are unique to this population, but “adult” injuries are also becoming more common in youth baseball. Hopefully, this provides coaches, parents, and young players with actionable advice to help them play a full, healthy season.

- Ensure Gradual Ramp-Up to Desired Pitching Volume/Intensity

With the spring season approaching, it is essential to make sure that we put our athletes in the best position possible to succeed. The offseason for young athletes is a unique situation as individuals may be starting from different places. Some athletes are finishing up their winter sport (basketball, track, hockey, etc.) and starting to transition into baseball activities, while others may have been working with pitching coaches or have been focused on baseball workouts at an earlier timeframe. Regardless, hopefully our athletes are in a position now where they are well-rested and ready to take on the preseason.

A key concept for throwing programs during this transitional stage is to allow for a gradual and progressive increase in throwing intensity and volume. Workload management for pitchers is not firmly established in the literature, but a good rule of thumb is to allow for a 1-2 week buildup in intensity/volume for every week that the athlete was shut down from throwing. Our primary goal is for the athlete to be ready for game-like intensity/volume by the time their season starts, not the first week of practice.

- Warm-up Effectively Before Throwing

It is essential for pitchers to participate in a thorough warm-up routine before bouts of throwing. The primary goals for a warm-up routine are to prime the systems of our body (nervous system, cardiovascular system, and musculoskeletal system) so that we can then perform movements required for our sport and allow for optimal performance. Pitching involves dynamic coordination and synchronization from our lower body, trunk, and upper extremities and our routine should reflect this. Our warm-up should also include exercises to ensure adequate mobility and contractibility of involved muscles (especially the rotator cuff, scapular muscles, and muscles of the elbow/forearm).

We don’t always have time to perform a 20-30 minute warm-up before practices or games but it’s the coach’s and athlete’s responsibility to make sure that they are ready to throw with max intent.

Here is an example of warm-up options that will prepare the athlete for the demands of throwing:

Movement Prep – Jogs, skips, bounds, shuffles, extensive pogos

Mobility (Upper body) – Dynamic shoulder hugs, dynamic shoulder swings, field goals, rotations at 90 degrees (palms up/down) x 15 reps for each

Mobility (Combined) – Open & close the gate hip opener, hip flexor steps with thoracic rotation, standing hip airplanes x 10 reps for each

Upper Extremity Muscle Activation – ER/IR tubes at side and 90 degrees (2 sets of 10), Hands clasped together isometric push in static position and with rotations (10 reps with 10 second push)

These warm-up exercises should be followed up with throwing with a gradual increase in intensity. Throwing should follow the progression of soft toss catch, long toss (with arc), and bullpen work.

- Monitor Pitch Count

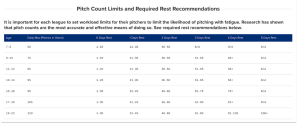

High pitch counts are among the biggest risk factors for upper extremity injuries in adolescent baseball players. Luckily, this is a modifiable risk factor that can be easily measured if coaches, parents, and the athlete themselves are paying attention. Pitch counts are the most accurate and effective way to monitor pitchers’ workloads and should be used at every level.

Here is a link to Pitch Smart USA which provides pitch count limits and required rest recommendations for athletes of different age groups: https://www.mlb.com/pitch-smart/pitching-guidelines.

- Be Cautious with Pitcher/Catcher Combos

According to a study in 2018, “pitchers who played catcher as a secondary position were at a 2.9 times greater risk of developing a throwing-related shoulder or elbow injury than pitchers who played a different secondary position” (Hibberd et al., 2018). This is most likely due to fatigue of the upper extremity accumulated from throwing without a period of rest (submaximal and maximal throws). While I am not saying that it is unsound for your athletes to play both of these positions, it is important to monitor their cumulative workload throughout a season rather than just pitch counts.

- Do NOT Pitch Through Fatigue or Pain

As previously stated, we should be following Pitch Smart USA guidelines for pitch counts and rest days with pitchers. In addition, coaches and parents should communicate with their athletes about arm fatigue and pain when throwing. Pitchers need to be monitored on a per-inning and per-game basis regarding arm fatigue. While the Pitch Smart USA guidelines are a great resource for in-season volume control, I would suggest being even more conservative during the preseason. Pitchers that throw through fatigue are 36 times more likely to incur an upper extremity injury (Fleisig & Andrews, 2006). Common signs of fatigue include decreased ball velocity, decreased accuracy, upright trunk during pitching, dropped elbow during pitching, or increased time between pitches. Pain, tenderness, or tightness in the shoulder, elbow, or forearm should always be treated seriously and the pitcher should not continue.

References:

Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. (2012). Prevention of elbow injuries in youth baseball pitchers. Sports Health, 26 (5), 419-24. doi: 10.1177/1941738112454828. PMID: 23016115; PMCID: PMC3435945.

Hibberd EE, Oyama S, Myers JB. (2018). Rate of Upper Extremity Injury in High School Baseball Pitchers Who Played Catcher as a Secondary Position. J Athl Train, 53 (5), 510-513. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-322-16. Epub 2018 May 17. PMID: 29771138; PMCID: PMC6107775.